Before opening my own eminent domain law firm, I briefly contemplated making some walking-around money with Amazon's Mechanical Turk, an online-odd-job-matchmaking service. This modern service takes its name from an 18th-century hoax designed to trick viewers into thinking a machine was able to play high-quality chess. Amazon's Mechanical Turk, which is not a hoax, requires users to complete Human Intelligence Tasks (HITs) for micropay - such as $.03 per HIT, with many thousands of HITs available.

Being adept at the Human Intelligence Task of math, I quickly determined my best short- and long-term prospects laid in finding real work, but thinking about the possibilities Mechanical Turk offered was interesting, if not disquieting.

Which brings us to a new article in The Atlantic, "A World Without Work," and the more scholarly article cited therein from the Oxford Martin School, "The Future of Employment - How Susceptible Are Jobs to Computerisation?" These futurist examinations of labor trends evaluate the possibility that computerization and mechanization will eliminate entire labor sectors, with the Atlantic article delving into the social ramifications of such an outcome.

The most interesting information in either article, for me, is the chart at the end of the Oxford Martin School article listing, in order, the 702 jobs computers are statistically most likely to eliminate from 1 (least likely) to 702 (most likely). Number 702, most likely to be eliminated, is telemarketers, which sounds wonderful until you recall these are jobs in which computers are likely to replace humans.

Lawyers (115) are relatively low on the list. Judges (271) are low as well, but less so than lawyers, which I will try to remember the next time a judge rules against me (Your time will come, your honor...) Unfortunately, politicians are not ranked.

Other legal jobs, paralegals and legal assistants (609), are likely to be computerized. Legal secretaries (672) are in worse danger.

What does this mean for you? I believe this ranking of lawyers is too optimistic and computerization is already driving down legal costs for many people. We already have automatic-legal-form programs and websites that will spit out a simple will or deed for a fixed fee. Avvo offers a service where you may cheaply ask real lawyers simple legal questions, but the time will come when a computer will answer those questions.

Before you agree to hire a lawyer for a simple question or task, see if there are lower-cost options available.

This trend towards computerization means also costs for actual lawyers should decrease as lawyers cut down on support staff.

This is occurring presently in Pima County. The Arizona Supreme Court mandated online electronic filing starting May 2015 for all civil cases in Pima County, which has cut out overnight the need for law firms to have runners physically take papers down to the courthouse for filing. The online filing system is so absurdly easy that most technologically-adept lawyers can file their own documents in five minutes, rather than hand them to a legal secretary for printing and filing.

Unfortunately, a utopian, completely lawyer-free society may well be far in the future. But computerization is sure to force lawyers - as much as any other workers - to continue to innovate and to prove their value over cheaper, more computerized options.

Opinion Note

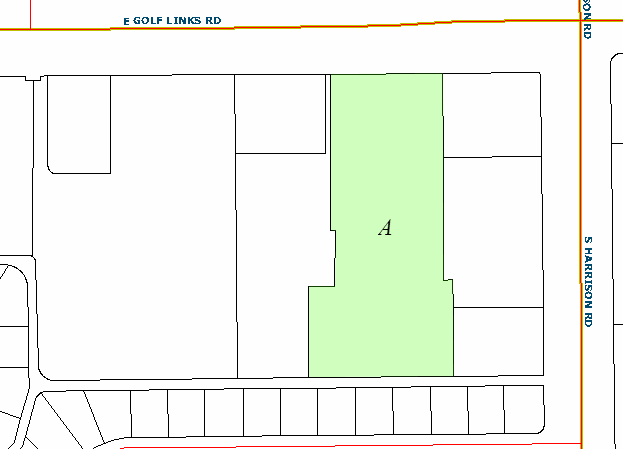

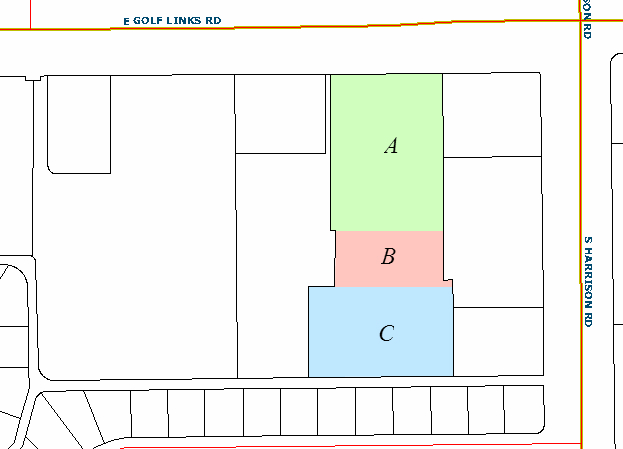

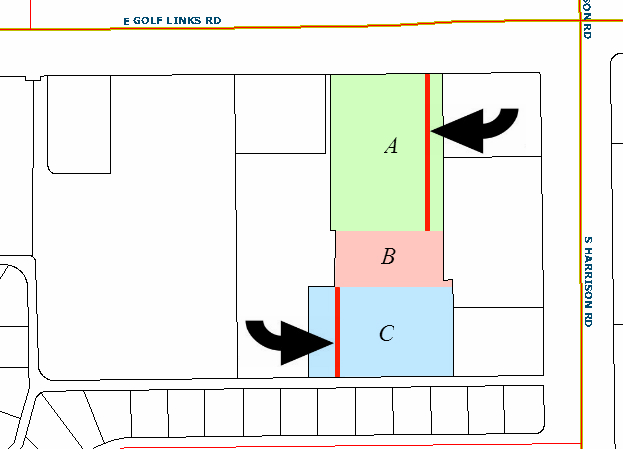

Arizona Court of Appeals, Division One - FIRST AMERICAN TITLE INSURANCE COMPANY v. JOHNSON BANK (June 30, 2015)

The Court of Appeals held the proper date of valuation to determine the loss in value to real property when an insured lender makes a claim on its own title insurance policy is the date of the lender's loan on the property, not the date of the foreclosure, if the foreclosure is the result of the very title defect giving rise to the insured's claim.