Arizona Court of Appeals Issues Federal Land Patent Easement Decision

/In Underwood v. Wilczynski, Division Two of the Arizona Court of Appeals issued an opinion clarifying certain rules applicable to easements granted pursuant to a federal land patent under the Small Tracts Act; 43 U.S.C. §§ 682a through 682e (repealed 1976). This case arose in Pinal County, so Division Two, located in Tucson, decided the appeal.

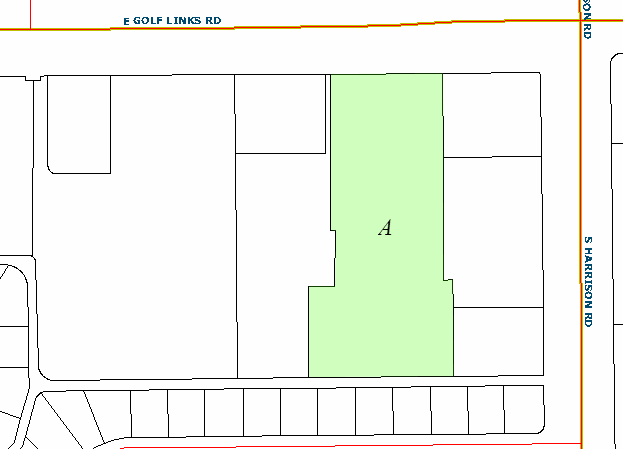

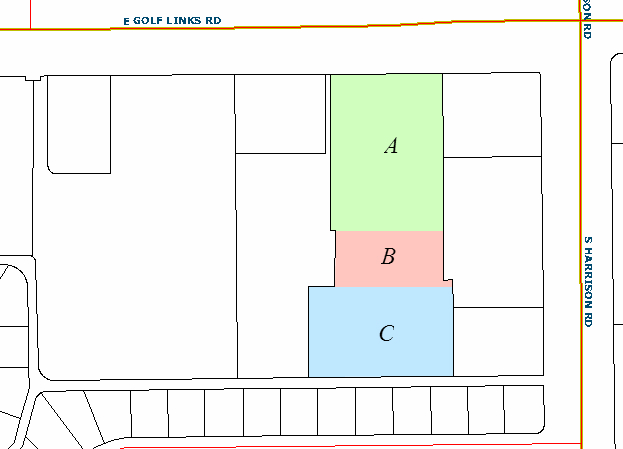

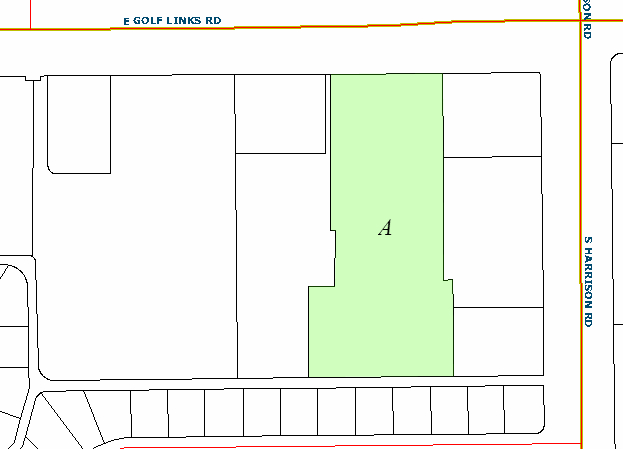

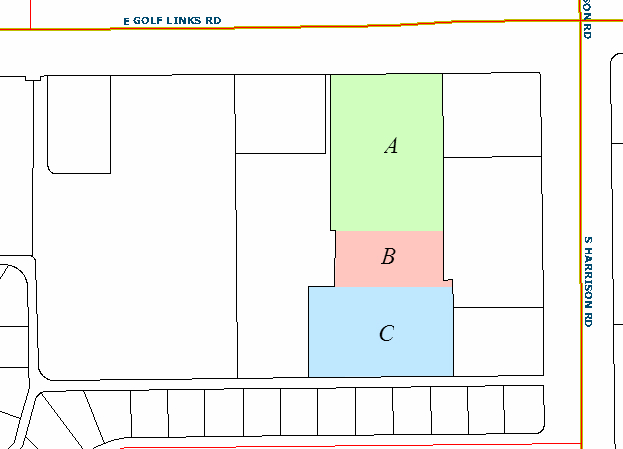

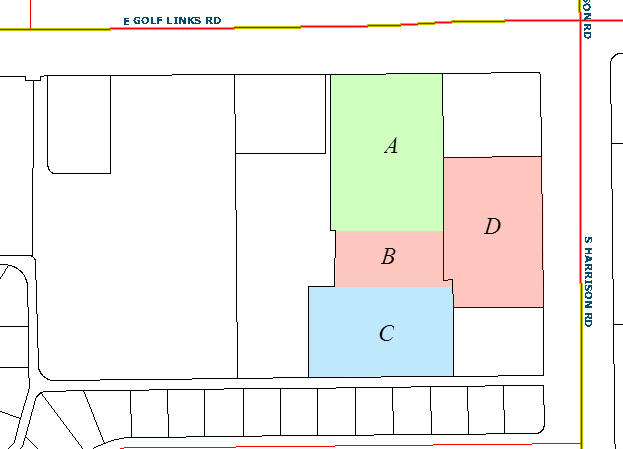

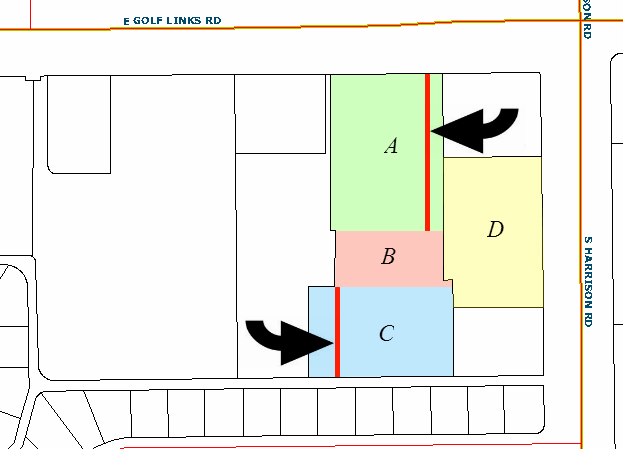

The case involved a dispute between three residential landowners: a trust, Underwood, and Wilczynski. Wilczynski owned landlocked property that required access through either the trust property or Underwood’s property. The Wilczynskis argued their property had legal access pursuant to 33-foot easements granted in federal land patents (FLPs) that ran along the boundaries of the trust and Underwood properties.

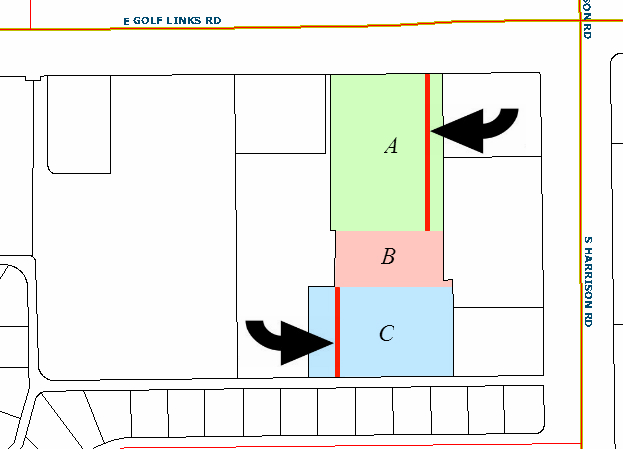

The Court of Appeals upheld the basis of the trial court’s ruling, which was summary judgment in favor of the Wilczynskis granting them access through the Underwood property (the trust did not dispute that Wilczynski could have access through the trust property). In upholding the ruling (and also vacating some portions of the actual judgment, which the Court of Appeals found had some technical errors), the Court of Appeals clarified some unique aspects of FLP easements:

FLP easements may only be used for access if necessary - if other physical and legal access to a parcel exists, the FLP easements are not necessary and therefore may not be used for convenience.

FLP easements, when necessary, may not necessarily be used to the full extent of their grant like other easements. In Underwood, the Court of Appeals found it was incorrect to say the Wilczynskis could use the entire 33-foot easement to enter the Wilczynski property when 33 feet was not necessary to construct an adequate access road. That is unlike other express easements that may be used as a matter of right up to the full extent of the express grant.

If a parcel needs to use an FLP easement out of necessity and has multiple FLP easement options to use for access (here, the Wilczynskis could have placed a road entirely on the trust property, entirely on the Underwood property, or half on both properties (this last option is the one the Wilczynskis chose)), the parcel needing access may choose where to place its access, and the burdened property owners (the trust and Underwood) cannot ask the court to force the parcel needing access to choose differently based on some external criteria.

Unique rules apply to FLP easements that make the legal rights and obligations of those easements slightly different than express easements in Arizona. The Court of Appeals does not issue a large number of opinions dealing with easements, and it was interesting to see how it dealt with these unique issues.